The world of pearls holds secrets far beyond their serene surfaces, where value is not merely assigned but microscopically earned. To the untrained eye, a pearl may simply be a lustrous gem, but its true worth is a complex tale written in layers, revealed through two critical characteristics: its orient and its overtone. These are not mere aesthetic features; they are the direct visual manifestations of the gem's internal architecture, a symphony of light and structure playing out on a microscopic stage.

At the heart of every pearl lies its genesis: the nacre. This substance, also known as mother-of-pearl, is the biological marvel secreted by a mollusk. It is not a monolithic layer but a intricate composite of crystalline and organic materials. The primary building block is aragonite, a form of calcium carbonate, arranged in microscopic hexagonal platelets. These platelets are akin to tiny, flat bricks. They are bound together by a organic protein glue called conchiolin. This combination of brittle mineral and flexible organic matter is fundamental; it is the reason nacre possesses both strength and a unique ability to interact with light. The mollusk deposits these bricks in a stratified, brick-wall-like formation, building the pearl layer by painstaking layer.

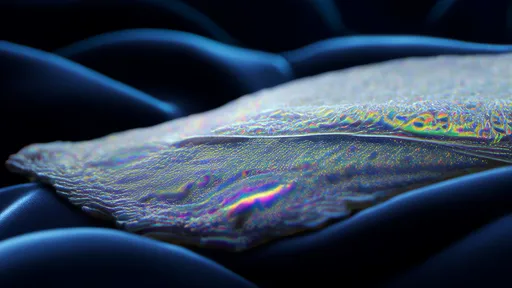

This meticulously layered structure is the canvas upon which light performs. When light strikes the surface of a pearl, a fraction of it is immediately reflected back to the eye, creating the initial sharp, mirror-like shine. This is the first act of the visual drama. However, the majority of the light does not simply bounce off; it penetrates the semi-translucent layers of nacre. As it travels through this labyrinth of aragonite crystals and conchiolin, the light is subjected to a series of complex interactions. It is refracted, or bent, as it passes from one crystal to another. It is diffracted, scattering around the edges of the microscopic platelets. Most importantly, a portion of the light is reflected not just from the surface, but from the innumerable internal boundaries between each minuscule layer of nacre.

The cumulative effect of this internal reflection is what pearl experts call luster, or more poetically, the pearl's "skin light" or orient. This is not a surface gloss but a deep, radiant glow that seems to emanate from within the pearl itself. The quality of this glow is directly and irrevocably tied to the microstructure. A pearl with high value possesses nacre that is exceptionally well-formed. The aragonite platelets are perfectly flat, uniformly sized, and aligned with breathtaking precision. This orderliness allows for maximum and coherent internal reflection. The light travels deep into the pearl and is reflected back out with minimal scattering, resulting in a sharp, intense, and deeply luminous glow. You can literally see your reflection on the surface of a high-luster pearl. Conversely, a pearl with poorly formed, disorganized, or thin nacre will appear chalky, dull, or plastic-like because the light scatters incoherently within its structure, failing to produce that coveted inner radiance.

While luster describes the intensity and quality of the light reflected, it does not tell the whole story of a pearl's color. This is where the second act begins, introducing the concept of overtone or companion color. If luster is the bright, white light from a projector, the overtone is the translucent color gel placed over it. It is a secondary, shimmering hue that seems to float over the pearl's primary body color. Common overtones include rosé, silver, ivory, and green. This phenomenon is also a direct consequence of the pearl's nanostructure. The same processes of interference and diffraction that create luster also act upon the different wavelengths of light that constitute white light.

As light waves travel through the nano-layers of nacre, they bounce off the internal surfaces. When two light waves meet, they can interfere with each other. If the peaks of the waves align (constructive interference), that particular color is intensified and visible to our eye. If a peak meets a trough (destructive interference), that color is cancelled out. The precise thickness of the aragonite platelets and the layers of conchiolin between them determines which wavelengths of light are amplified and which are suppressed. A specific, consistent spacing will consistently amplify, for example, pink wavelengths, resulting in a rosé overtone shimmering over a white body color. The thinner and more consistent the layers, the more vivid and defined the overtone. This is why the finest Akoya pearls, renowned for their exquisite rosé and silver overtones, have some of the most perfectly formed and regular nacre in the gem world.

The interplay between the pearl's base body color—influenced by the mollusk species and its environment—and the overtone generated by its structure creates a depth and complexity of color unmatched by any dyed gem. It is a dynamic visual effect that changes subtly with the angle of light and the perspective of the viewer, a living iridescence that no photograph can truly capture. This is the play-of-color that connoisseurs cherish.

Therefore, the journey to assessing a pearl's value is a journey into its soul, viewed through a loupe. An appraiser or knowledgeable buyer does not just look at a pearl; they read it. They roll it slowly under a light source, observing how the glow behaves. They search for that sharp, deep reflection—the sign of superior, well-structured nacre. They then tilt the pearl, watching for the shimmering dance of overtone colors across its surface, assessing their clarity and strength. A strong, sharp luster combined with a clear, defined overtone is the hallmark of a pearl with exceptional microstructure, and therefore, high intrinsic value. These pearls are typically the result of healthy mollusks in pristine environments, given ample time to deposit their nacre with perfection. They are rare and command prices that reflect their biological and optical perfection.

In the end, a pearl's beauty is far more than skin deep. Its allure is a direct physical manifestation of its hidden architectural splendor. The orient and the overtone are not merely decorative terms from a jeweler's lexicon; they are the language of light, spoken through the exquisite, microscopic lattice of nacre. To understand them is to understand the very essence of the pearl's value, appreciating it not just as a gem, but as a natural wonder of structural engineering. This deep, scientific appreciation separates a simple accessory from a timeless treasure, anchoring its worth in the immutable laws of physics and biology.

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025