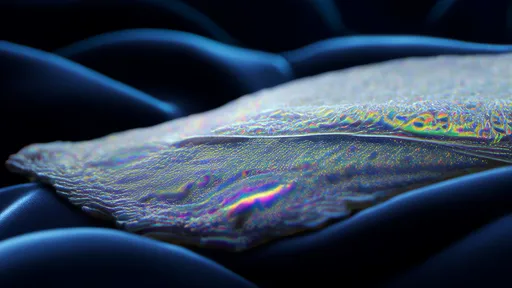

The shimmering promise of recycled precious metals from electronic waste presents a paradox. While the environmental and economic benefits are widely championed, a fundamental question lingers in the corridors of refineries, boardrooms, and ethical marketplaces: how can one irrefutably prove its origin? The journey from a discarded smartphone to a gleaming bar of gold is fraught with logistical and evidential challenges that threaten to undermine the very credibility of this green endeavor.

At the heart of the certification dilemma lies the chaotic and fragmented nature of the global e-waste stream. Unlike a cleanly mined ore from a single, well-documented geological source, electronic waste is a mongrel mix. A single shipment to a recycling facility can contain circuit boards from a dozen different manufacturers, laptops from various generations, and phones from across the globe, all blended into an anonymous heap. This comingling at the source destroys any inherent provenance. There is no "birth certificate" for a specific gram of gold once it has been dissolved into a chemical bath alongside gold from thousands of other devices. The material loses its identity, becoming a homogeneous part of a whole, its history erased by the very process that liberates it.

This anonymity is compounded by the complex and often opaque supply chains that feed recycling plants. E-waste frequently passes through multiple hands—informal collectors, aggregators, brokers, and international exporters—before reaching a certified high-tech facility. Each transfer is a potential point where non-recycled, virgin, or conflict-sourced material could be introduced, either by accident or with malicious intent to launder its origin. Without a robust, tamper-proof system to track the waste from the point of discard to the final refinery, the chain of custody is broken. The reclaimer is thus often left to take a supplier's word on faith, a precarious foundation for building a certified, premium product.

Current certification schemes, while a step in the right direction, grapple with these inherent difficulties. Many rely heavily on mass balance accounting, a bookkeeping method that tracks the total amount of recycled content through a production run rather than attributing it to a specific product batch. Think of it like adding a bottle of recycled water to a large tank of virgin water; you can claim the entire tank has a percentage of recycled content, but you cannot draw a glass and swear that particular water is the recycled one. For many end-users, especially in industries like electronics or jewelry where ethical sourcing is paramount, this lack of granular, physical guarantee is a significant drawback. It feels less like a certification and more like an estimate.

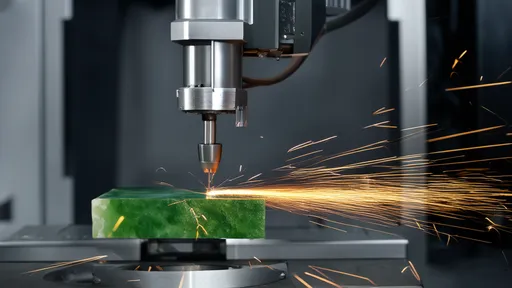

The technological race to solve this evidentiary crisis is on. One of the most promising frontiers is the concept of introducing synthetic tracers or DNA markers. The idea is to apply a unique, inert chemical signature to electronic components at the manufacturing stage. This marker would survive the product's lifespan and the brutal recycling process, allowing refiners to later detect its presence through advanced spectrometry. Finding the marker would be the definitive proof that the resulting metal once resided inside a consumer gadget. While promising, the hurdle is immense, requiring unprecedented global cooperation among fiercely competitive electronics giants to standardize and implement such a system.

Other ventures are looking towards blockchain technology to create an immutable digital ledger for physical goods. The theory is that each device or batch of e-waste could be logged onto a blockchain at the point of collection, with every subsequent transaction—transport, processing, refining—recorded as a new block. This would create a transparent and unforgeable chain of custody. However, the critical challenge remains the initial, physical step: how to seamlessly and reliably connect a physical, often shredded, pile of waste to its digital twin on the blockchain without error or fraud. The gap between the digital and physical worlds is where trust can still evaporate.

Beyond technology, the economic reality poses its own barrier to certification. Implementing these advanced traceability systems—whether chemical tracers or digital ledgers—adds significant cost to the recycling process. This elevated cost must then be absorbed by the market. For recycled precious metal to compete with traditionally mined metal, consumers and manufacturers must be willing to pay a premium for verified circularity. This requires a shift in market values, where provenance is valued as highly as purity and price. Without clear demand and willingness to pay for certified recycled content, the economic incentive to develop and deploy these complex systems remains weak.

The role of consumer and corporate demand cannot be overstated. The push for verifiably recycled metals is ultimately driven by the end-user's desire for sustainable and ethical products. As this demand grows louder and more specific—moving from a vague desire for "recycled content" to a demand for "provenably recycled content"—it forces the entire supply chain to innovate. Corporations under pressure to meet ambitious ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) goals are becoming the most vocal clients for recyclers who can provide not just metal, but proof. This market pressure is perhaps the most powerful catalyst for overcoming the current certification dilemma.

In conclusion, the challenge of certifying recycled precious metals is a intricate puzzle with technical, logistical, and economic pieces. It is not a problem with a single silver bullet solution. Overcoming it will require a concerted effort: technological innovation to provide physical proof, systemic overhaul to ensure supply chain transparency, and a maturation of the market to value and pay for verified sustainability. The goal is to transform the current system, which often operates on a foundation of trust and estimation, into one that runs on irrefutable evidence. Until that happens, the full potential of urban mining—turning our endless stream of e-waste into a trusted, ethical source of wealth—will remain tantalizingly out of reach, its brilliance dimmed by the shadow of doubt.

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025