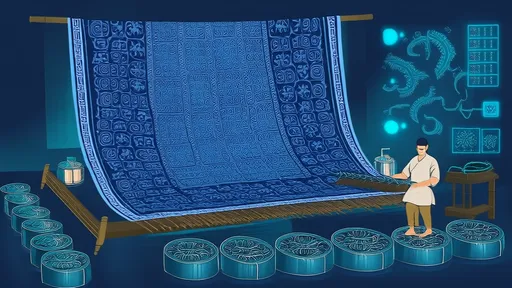

The ancient art of Nishijin-ori, or Nishijin weaving, has long been celebrated as one of Japan’s most exquisite textile traditions. Originating in Kyoto’s historic Nishijin district, this luxurious craft has been perfected over centuries, producing fabrics that adorn the robes of emperors, the vestments of Shinto priests, and the collections of discerning connoisseurs worldwide. Among its many breathtaking techniques, one stands out as particularly mesmerizing: the weaving of 0.1-millimeter gold foil into silk. This delicate process transforms already opulent textiles into shimmering masterpieces, blending human ingenuity with the brilliance of nature’s most coveted metal.

The incorporation of gold into Nishijin-ori is not merely decorative—it is a testament to the weaver’s patience, precision, and reverence for tradition. The gold foil, painstakingly hammered to a near-translucent thinness, is cut into slender threads before being entwined with silk. Unlike gilding or embroidery, where metal is applied superficially, this method embeds gold directly into the fabric’s structure. The result is a textile that catches light with every subtle movement, its golden threads glowing as if illuminated from within. To witness a kimono woven with this technique is to understand why Nishijin-ori has been called "the poetry of the loom."

What makes this practice even more remarkable is the fragility of the materials involved. Gold foil of such thinness is notoriously difficult to handle, prone to tearing at the slightest mishandling. The silk, too, demands respect—its fibers must be tensioned perfectly to avoid breakage during weaving. Master weavers, often with decades of experience, work in near-silent studios, their looms adjusted to a delicacy unmatched in modern textile production. Every pass of the shuttle is a calculated risk, every knot tied with the awareness that a single error could unravel hours of labor. Yet, when executed flawlessly, the woven gold becomes inseparable from the silk, enduring for generations without tarnishing or fading.

Historically, this technique was reserved for the most elite patrons—shoguns, aristocrats, and temples—serving as both artistic expression and political statement. A single bolt of gold-woven Nishijin fabric could equal the annual income of a prosperous merchant, making it as much a currency of power as a medium of beauty. Today, while synthetic alternatives exist, purists insist on traditional methods, sourcing gold from the same Kyoto suppliers who served the Edo-period nobility. The process remains largely unchanged: the foil is still cut by hand, the looms are still wooden, and the weavers still rely on instinct honed through years of apprenticeship.

Modern applications of this artistry extend beyond ceremonial wear. Contemporary designers collaborate with Nishijin masters to create striking installations, architectural panels, and even avant-garde fashion that bridges past and future. Yet regardless of its form, each gold-woven piece carries with it the weight of history—a shimmering thread connecting today’s admirers to the craftsmen of centuries past. In an age of mass production, Kyoto’s 0.1-millimeter gold foil weaving stands as a defiant celebration of slowness, proving that some forms of radiance cannot be rushed.

Behind every square centimeter of gold-woven fabric lies an unspoken philosophy. The Nishijin tradition teaches that true luxury is not about ostentation, but about the invisible labor that makes excellence seem effortless. It is a reminder that beauty often resides in constraints—the limitation of the loom’s width, the fragility of the foil, the human hand’s finite dexterity. Perhaps this is why these textiles compel such reverence: they are not merely objects, but physical manifestations of discipline, a alchemy of patience and preciousness that no machine can replicate. As long as there are hands to weave and eyes to marvel, Kyoto’s golden threads will continue their quiet, luminous dance through time.

By /Aug 13, 2025

By /Aug 13, 2025

By /Aug 13, 2025

By /Aug 13, 2025

By /Aug 13, 2025

By /Aug 13, 2025

By /Aug 13, 2025

By /Aug 13, 2025

By /Aug 13, 2025

By /Aug 13, 2025

By /Aug 13, 2025

By /Aug 13, 2025

By /Aug 13, 2025

By /Aug 13, 2025

By /Aug 13, 2025

By /Aug 13, 2025

By /Aug 13, 2025

By /Aug 13, 2025

By /Aug 13, 2025

By /Aug 13, 2025